Turandot

Giacomo PucciniJuly 26 – August 24 2025

“Turandot is released from her cage at skäret – powerful and magnificent tale of twisted love

That’s how Nya Wermlands-Tidningen describes Turandot, this year’s summer opera at Skäret, in its review. Over the final weekend of July, two distinguished casts each had their own premiere of the production, and the reviews have been glowing. Here is what the critics had to say:

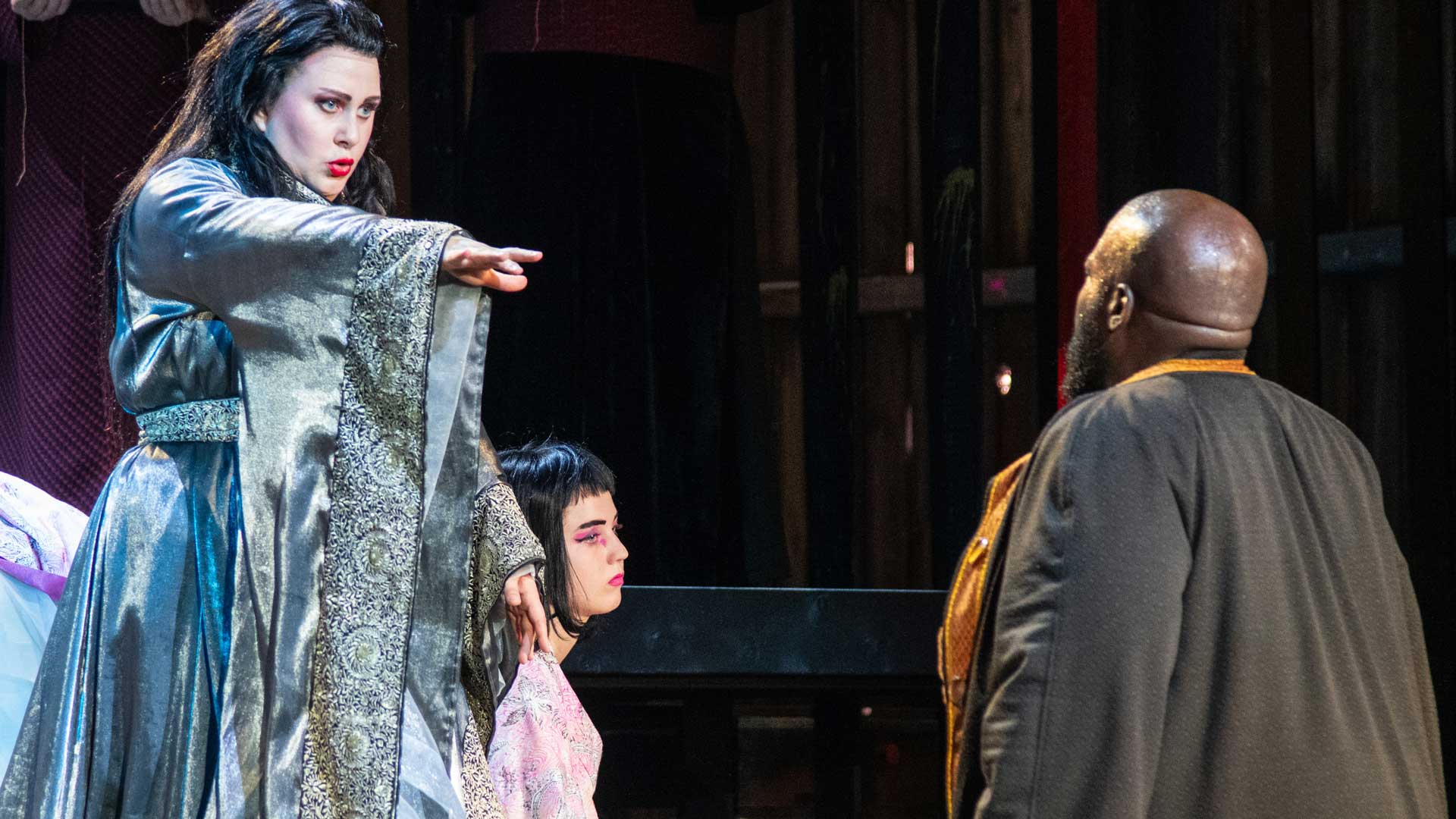

“Polish Lucyna Jarzabek can fire off Turandot’s icy proclamations with just the right heat in the cold.”(Dagens Nyheter)

“Very few singers can meet the demands of the roles of Calaf and Turandot, but Errin Duane Brooks and Léa Bianco Chinto do so in an enchanting and magnificent way.” (Falu-Kuriren)

“Turandot’s heart is released from its icy cage, and Opera på Skäret has once again shown that world-class opera can flourish even on the edge of a forest lake.”(Nya Wermlands-Tidningen)

“The title role requires a laser-sharp, preferably armor-piercing soprano, and the French-Italian singer Léa Bianco Chinto is exactly that. She has a truly breathtaking turbo mode in her highest register that cuts like a hot knife through orchestral butter. Spectacular.” (Falu-Kuriren)

“Conductor Lorenzo Coladonato does a brilliant job with the Swedish Chamber Orchestra. There is an excellent balance between soloists, chorus, and orchestra.” (Nerikes Allehanda)

“Lilla Horti as Liù has a voluminous voice that truly carries and reaches the audience, and her vocal interpretation is excellent.”(Falu-Kuriren)

“It is Kseniya Bakhritdinova who earns the first big spontaneous applause of the premiere night with her sparkling voice. It’s so beautiful it brings tears.”(Nya Wermlands-Tidningen)

“The American tenor Errin Duane Brooks possesses the rare power to truly soar. He deserves a nine out of ten for his rendition of ‘Nessun dorma.’ World class.” (Falu-Kuriren)

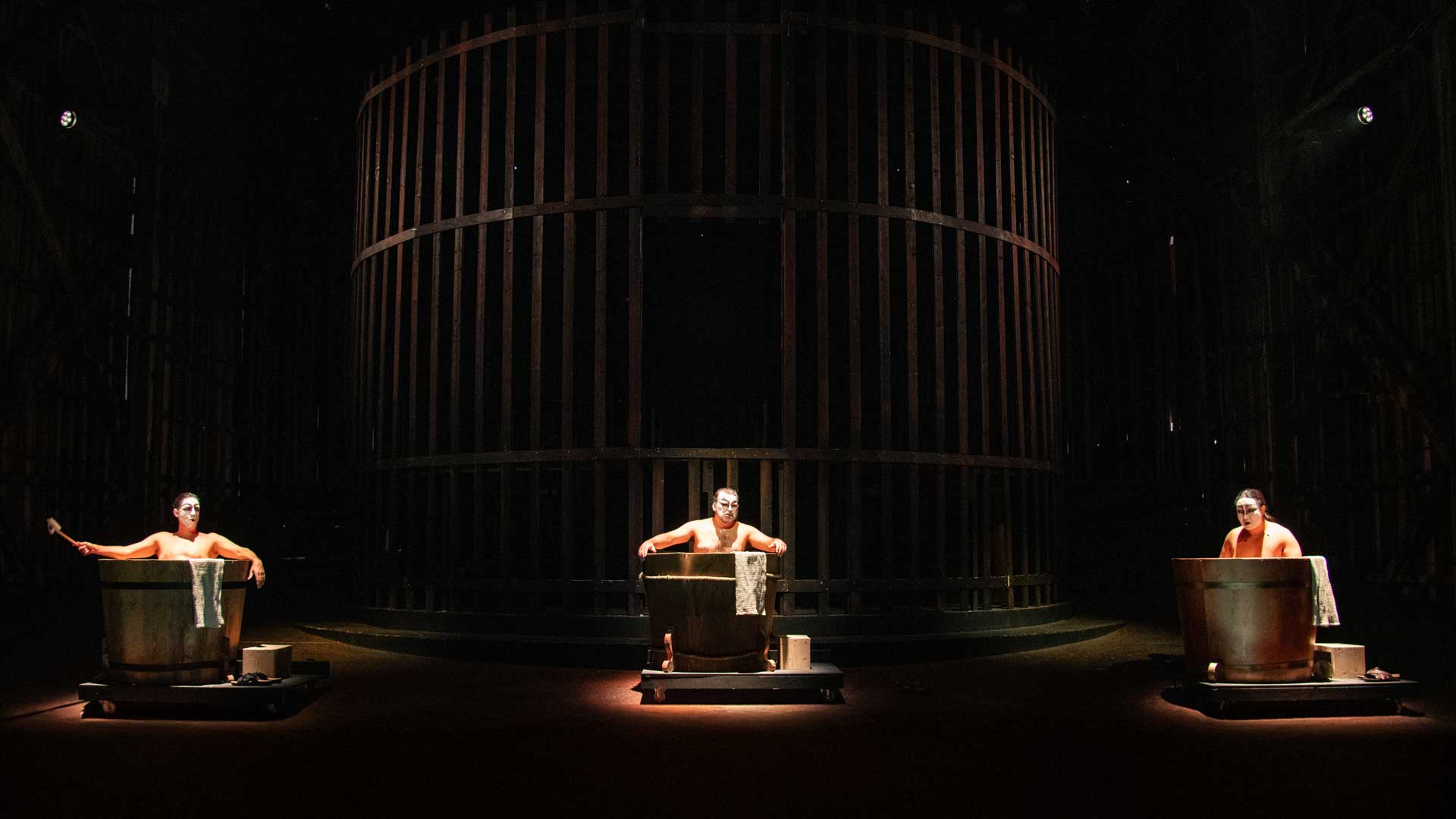

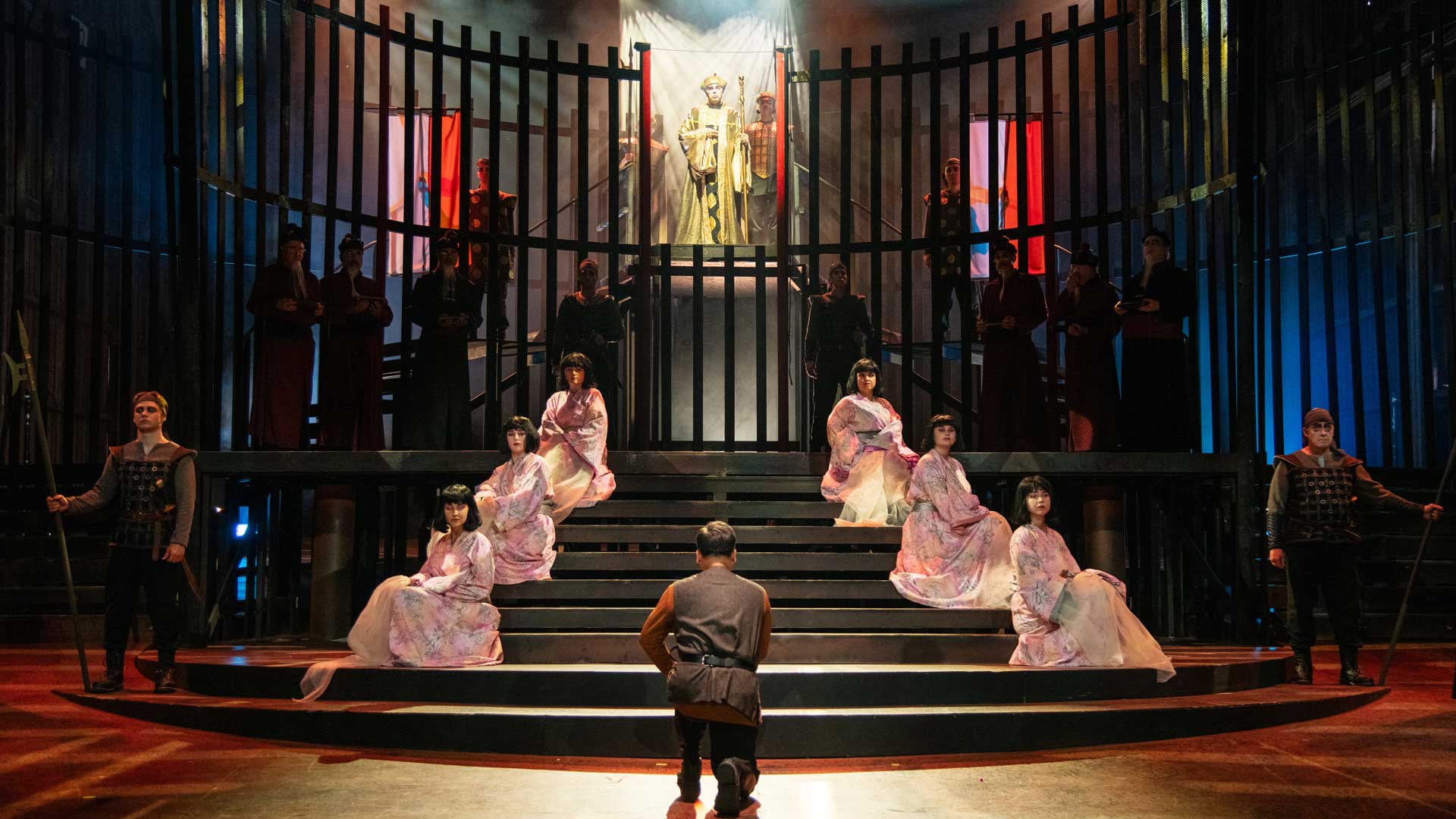

“When set designer Sven Östberg is at work, you know you won’t get gaudy dragons in gold and red. His solution is to make the palace a cage—or rather a cage within another cage. A simple yet effective concept where the wooden lattice blends well with the surrounding timber warehouse. Inside, Turandot is kept, guarded by sentinels with spears. Added to this is Magdalena Stenbeck’s costume work, with dramatic solutions where colours highlight the social hierarchy. Together with Stephanie Metzner (makeup) and Maria Ros (lighting), they’ve created a vivid and powerful stage design that interacts with Puccini’s fantastic music. When Turandot enters bathed in light in her silver dress, it all becomes a truly mighty experience.”

(Nerikes Allehanda)

“Turandot becomes a mighty experience.” (Nerikes Allehanda)

“Opposite the murderous Turandot stands the kind-hearted servant Liù, who sacrifices her life – she too a twisted interpretation of ‘love.’ For her, Puccini composed melting legato phrases, which Kseniya Bakhritdinova delivers beautifully.” (Dagens Nyheter)

“Korean James Lee hits his high B- with brilliance.”(Dagens Nyheter)

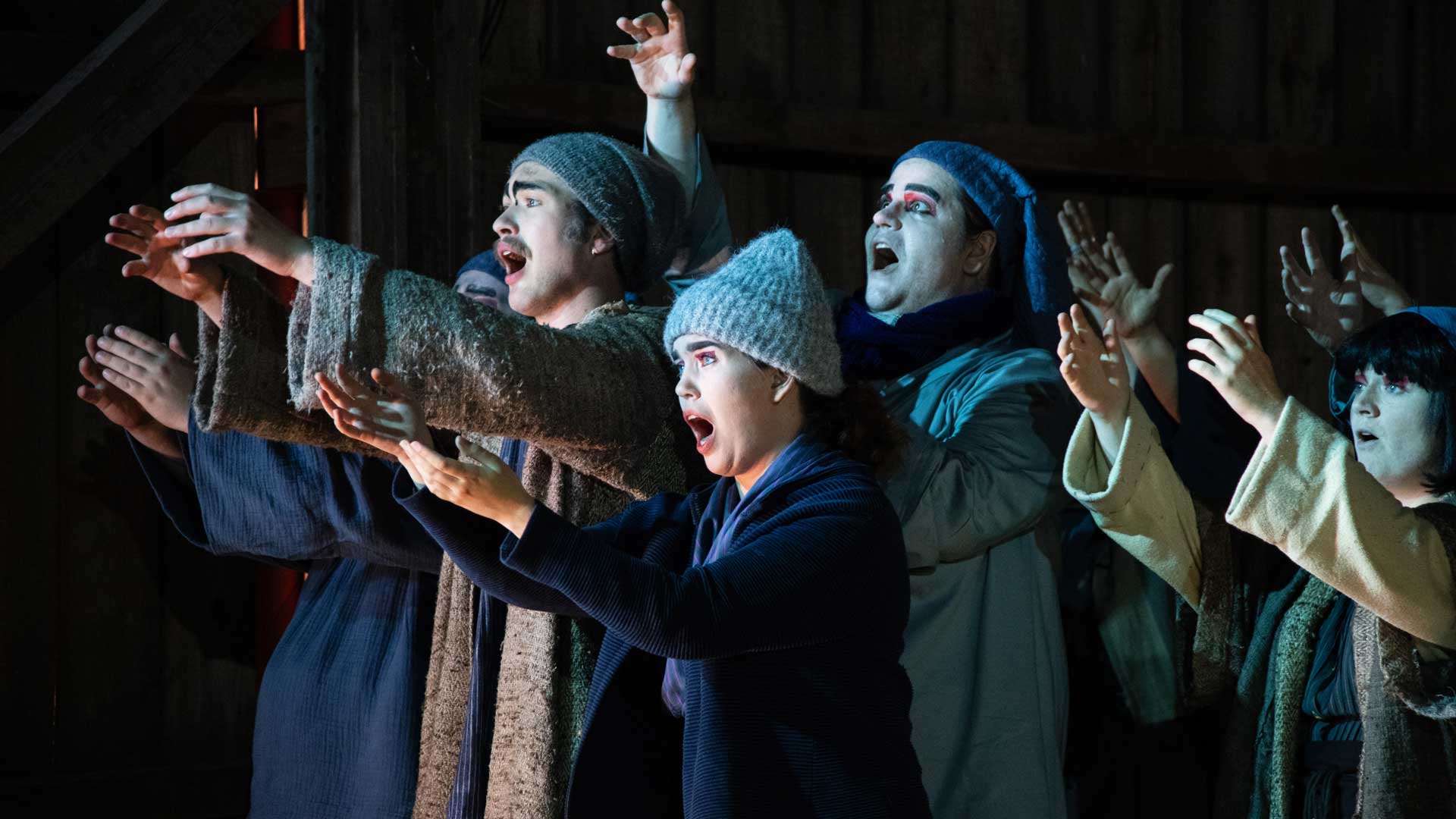

“Both the in-house chorus and the Swedish Chamber Orchestra maintain a high artistic standard. Coladonato brings out the refined detail in Puccini’s pentatonic Chinese inspired themes.” (Dagens Nyheter)

Turandot

Turandot became Giacomo Puccini’s final opera and is today immensely beloved worldwide. This is the operatic tale of an oppressed people under an imperial dynasty in China. The merciless Princess Turandot is set to marry according to tradition but refuses to face the same fate as an ancestor who was murdered after getting married. She does not want to be reduced to being subordinate to a man and has therefore, in order to delay marriage, imposed the condition that a suitor must correctly answer three riddles. If the suitor fails, he is executed.

Puccini wrote this opera while he was very ill and never managed to complete the work. Instead, his student Alfano finished it according to Puccini’s notes. Since its premiere in 1926 at La Scala in Milan, Turandot has held an unquestioned place in the repertoire of major opera houses. The magnificent music and the setting at the centre of power in China is very captivating, not least through the challenging vocal parts that demands dramatic voices.

By the summer of 2025, we will be able to offer our audience this beloved opera, with the famous aria Nessun dorma, in one of the world’s most unique opera houses, a former sawmill located by the shore of a vast lake, now famous for its acoustics.

Soloists in the production of Turandot

Opera is a truly wonderful art form, but it also places great demands on its singers. That’s why we at Opera på Skäret always work with two casts of soloists – and why we have not just one, but two premieres. Information about which singers are in each cast will be shared at a later date.

Soloists

Turandot – Lucyna Jarząbek / Léa Bianco Chinto

Calaf – Errin Duane Brooks / James Lee

Liù – Kseniya Bakhritdinova – Kravchuk / Lilla Horti

Timur/Un Mandarino – Staffan Liljas / Youngkug Jin / Seth Sundman (14 aug)

Ping – Anton Eriksson / Seth Sundman (7 aug)

Pang – Alexander Grove / Otto Larsson (21 aug)

Pong – Hwapyeong Gwon / Alexander Jönsson (14 aug)

The Emperor – Thomas Bärlin / Samuel Karlberg

The Prince of Persia – David Bergman / Christopher Kingdon

Handmaidens – Isabella Rubin, Alva Andersson, Sofie Westerberg, Lilly Broberg

ARTISTIC PRODUCTION

Director – Lev Pugliese

Conductor– Lorenzo Coladonato

Set Designer – Sven Östberg

Costume Designer – Magdalena Stenbeck

Makeup & Wig – Stephanie Metzner

Lighting Designer – Maria Ros

Repetiteur – Bengt-Åke Lundin

Repetiteur – Samuel Skönberg

Chorus Master – Jonatan Lönnqvist

Repetiteur Chorus – Mats Johansson

The singing ensembles will perform the following dates (subject to change)

July 26, Aug 2, Aug 7, Aug 10, Aug 16, Aug 21, Aug 24

Turandot – Lucyna Jarząbek

Calaf – James Lee

Liù – Kseniya Bakhritdinova-Kravchuk

Timur – Youngkug Jin

Mandarino – Staffan Liljas

Ping – Anton Eriksson* (except Aug 7)

Pang – Alexander Grove

Pong – Hwapyeong Gwon* (except Aug 21)

The Emperor – Thomas Bärlin

Prince of Persia– Samuel Karlberg

Handmaidens –

Isabella Rubin, Sofie Westerberg,

Alva Andersson, Lilly Broberg

*On Aug 7, Seth Sundman will sing the role Ping

*On Aug 21, Otto Larsson will sing the role Pong

July 27, Aug 3, Aug 9, Aug 14, Aug 17, Aug 23

Turandot – Léa Bianco Chinto

Calaf – Errin Duane Brooks

Liù – Lilla Horti

Timur – Staffan Liljas

Mandarino – Youngkug Jin* (except Aug 14)

Ping – Anton Eriksson

Pang – Alexander Grove* (except Aug 14)

Pong – Hwapyeong Gwon

The Emperor – David Bergman

Prince of Persia – Christopher Kingdon

Handmaidens –

Isabella Rubin, Sofie Westerberg,

Alva Andersson, Lilly Broberg

* On Aug 14, Alexander Jönsson will sing the role Pang

* On Aug 14, Seth Sundman will sing the role Mandarino

The Swedish Chamber Orchestra

The Opera på Skärets Chorus

26 July – 24 August

Performance duration: approx. 3 hours, including a 45-minute intermission.

about the direction

Our exploration of Turandot does not depart from the grand, ceremonial squares of Beijing, but venturing deep within the intricate, frozen labyrinth of the Princess’s psyche. As she sings “In questa reggia”, her voice echoes through the vast halls of the Imperial Palace, but it is within the far more impenetrable fortress of her own inner world — a citadel of ice, untouched and suspended in time — that the opera’s true, visceral drama unfolds. The directorial vision of this performance seeks to move beyond any merely ornamental or stereotyped interpretation, delving, instead, into a territory where characters cross even the terrain of the soul

Turandot, in this conception, is far more than just a symbol of frigid power; she is a profoundly wounded soul, her famed cruelty, not an innate malice but an ossified carapace, an extreme psychological defence mechanism forged in the spectral fires of an inherited trauma — the unresolved horror of her ancestor Lo-u-Ling’s rape. Her decree to execute suitors becomes, symbolically, a desperate attempt to exorcise the repetition of this ancestral physical and emotional violation. Turandot is, hence, a psychic projection of this long-buried agony. Her arrested emotional development and her rigidity are the only means of survival she has ever known. Visually, her initial presence appears immobile, almost otherworldly, but, enshrined within a sculptural, wearable structure of pale, iridescent metals — not simply a costume — it is an incarnation of her emotional inaccessibility, a magnificent confining armour. Inside this frozen exterior there is a pulsing hidden core, a secret vermillion lining, symbol of repressed life, of denied eros, of the dormant woman, the barely alive ember of the life force she so vehemently denies.

Into this glacial realm appears Calaf, the unknown prince; a figure often perceived as the archetypal hero. We are compelled to interrogate his arrival, his relentless pursuit. Is his quest for Turandot’s hand born from an irresistible coup de foudre, or is there a potent undercurrent of a conqueror’s ambition, a desire to vanquish the unvanquishable, to solve the insoluble? Whilst his courage is beyond dispute — he willingly stakes his life — his initial attitude could be seen as a form of siege. The three enigmas he so deftly unravels are not merely intellectual puzzles, even if doubtlessly they are keys, but they also function as battering rams against the gates of Turandot’s formidable psychic defences. Calaf embodies a fascinating ambiguity: a man driven by a potent mixture of ardour and, perhaps, an unconscious desire for domination. He begins to shed the mantle of conqueror, to transcend this heroic yet potentially predatory stance, only when he discloses his own mystery — his name — thereby accepting the possibility of being put to death. This gesture, deceptively simple, becomes the opera’s only act of true love: love as respect, love as the recognition of the right to freedom, not as an imposition of duty, a debt, a profound act of vulnerability that shifts the dynamic from “winning” Turandot to the possibility of “reaching” her.

The true catalyst, the emotional fulcrum that balances the entire opera and the key figure within this dynamic, is the incandescent Liù. Her psychological landscape is the stark antithesis of Turandot’s frozen grandeur. Unlike the Princess, Liù does not repress, she loves. She loves with the fragile but steadfast strength of one who possesses no armour. Her love for Calaf is not a demand, not a strategy, it is a pure, unwavering, silent emanation of her being, a gentle stream with the power to erode even the hardest stone. Liù asks for nothing, yet gives everything. In her, we witness the devastating beauty of selfless devotion, a quiet strength ultimately more potent than all the imperial power of Beijing. Her significance transcends that of a mere “faithful slave girl”; she is the embodiment of unshielded humanity, the keeper of a warmth that Turandot had long since extinguished within herself. The psychological impact of Liù’s sacrifice upon Turandot is, in this vision, the absolute core of the opera’s dramatic transformation. Her death is not a mere lyrical sacrifice, it is an archetypal gesture, a rupture that sets off Turandot’s crisis. It is not Calaf’s triumphant solving of the riddles, nor his kiss, that begins to thaw the icy princess, but the devastating, irrefutable evidence of Liù’s love — a love so profound it embraces death rather than betray the beloved.

Visually, the moment of Liù’s demise should be one of stark, arresting contrast, rendered through an almost physical silence. The preceding clamour and tension gives way to a stage that empties, where bodies freeze, where time itself appears suspended. The light contracts, focusing intensely first on Liù, then on Turandot’s visceral reaction, as if the world is holding its breath. It is in this sacred, suspended moment, witnessing an emotional truth she cannot deny or deflect with cruelty, that the first true fissures appear in Turandot’s armour. Liù’s death is not a defeat, but a ferocious, beautiful victory of the human heart, planting a seed of empathy in the barren terrain of Turandot’s soul. There, without words, Turandot begins to split inside — not because she is convinced by Calaf, but because she is utterly disarmed by Liù.

The Alfano ending, therefore, takes on a particular, renewed resonance within this psychological framework. Turandot’s utterance of Calaf’s name — “Il suo nome è Amor!” — is no sudden fairy-tale capitulation or romantic surrender, it is, rather, the culmination of a slow inner combustion, a seismic internal shift, a painful and hesitant emergence from a self-imposed prison. It is the first, tentative word spoken in a new language of feeling, a language whose grammar was taught by the silent sacrifice of Liù and the vulnerable offering of Calaf. The grand, collective joy of the finale is thus underscored by a more intimate, fragile hope. We do not necessarily know whether she will be capable of truly loving, or of living within that feeling, but it is her first step beyond the armour. On stage, her sculptural structure might open — not fall, nor shatter, but blossom like a flower, revealing what had until then remained hidden. As with every healing process, love does not rescue, it liberates. Turandot, then, is not so much a Chinese fairy tale, but rather a psychic myth — a disclosure of the power trauma holds, of how it can freeze the soul, and of the fear of tremendous risk (inherent) in opening oneself to another. There is no easy redemption, no guaranteed happy ending, only the deeply human courage to dare to feel.

Lev Pugliese

Director

ABOUT THE MUSIC

Puccini’s last opera offers us many points for reflection. I believe that at least three of these are of great importance. I am pleased to be able to share them with you, in the hope that they may help us to listen consciously to the music and enjoy the performance more.

Firstly, it is important to emphasise the radical novelty of Turandot’s musical language, a language that is avant-garde in every respect. Puccini’s harmonies are expanded, the rhythm sometimes becomes percussive, the voices are pushed into extreme tessituras. All of this is combined with an exceptional mastery of orchestration, that is invariably placed at the service of the drama. Puccini, who was always driven by a desire for renewal, reaches here the apex of his compositional mastery and leaves us a masterpiece that serves as a link between two eras, romanticism and contemporaneity.

Secondly, it should be noted that Turandot is the only Puccini opera in which the chorus plays a main role from the first to the last page. Often this aspect does not receive due attention; one prefers to emphasise the more technical compositional aspects mentioned above. Puccini, a cosmopolitan and curious artist, places himself at the forefront of the increasing interest in musical realism, showing that he was inspired by the example set by another choral masterpiece, such as Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov. Furthermore, he recaptures and breathes new life into the function of the chorus as it was in Greek tragedy, where it acted as a bridge between the audience and the characters in the action.

In this brief reflection, however, I would like to focus more on a third aspect, which I find to be the most interesting: the blending of different compositional styles in Turandot. Three can be identified:

1) The dissonant style: this represents the big innovation in Puccini’s musical journey. He chose to embrace a newfound boldness in musical expression. This approach is marked by the presence of harmonic tensions and harsh dissonances, which were uncommon in his earlier works. The rhythm becomes increasingly obstinate and percussive, contributing to the overall sense of intensity and modernity. An excellent example of this new style can be found right at the very beginning, during the Mandarin scene.

2) The exotic style: this had already been experimented with by Puccini in Madama Butterfly. Now he goes further and uses this style with great mastery by incorporating a variety of exotic scales from non-European musical traditions. Examples abound; one of the most effective can be found in the first act, when the Prince of Persia is led to his execution. The procession is accompanied by a splendid melody that uses the diminished Lydian scale, which has an oriental flavour and conveys a deep sense of sadness.

3) The romantic style: this is Puccini’s distinctive signature, which is already evident in his first major success, Manon Lescaut (1893). It is the style of the aria ‘Nessun dorma’, for example, with his gorgeous melody and lush orchestration. This is also the style of the finale primo, which is built in a quite traditional way and is based on a typical Puccinian undulating melody.

These three styles have been fused together to create a coherent and organic work of art. This is exactly what fascinates me most: how Puccini managed to achieve such a homogeneous result. ‘In varietate concordia’.

One final point to consider is that Turandot is an unfinished opera. Puccini did not succeed to complete it, and in my opinion this was not due to his death in 1924, but rather because he could not overcome a dramaturgical dilemma. However, this theme would take us too far.

The absence of the finale poses a number of problematic choices, the first and most important of which is whether to end the opera where Puccini left off, or to use one of the two available completions, by Franco Alfano or Luciano Berio. For this new production Opera på Skäret has opted for the so-called traditional version, with the final duet completed by Franco Alfano. His completion was then considerably shortened by Arturo Toscanini, who conducted the world premiere in 1926. This has become the most common choice over the last hundred years.

But how would Puccini have ended the opera? Perhaps the irresistible fascination of this masterpiece lies in this very last unanswered question.

Lorenzo Coladonato

Conductor

About the set design

What kind of world might have shaped the characters in the opera Turandot?

In the opera Turandot, it is hard to find, among the main characters, anyone you’d gladly invite over for tea. They all seem brutal and deeply egocentric—perhaps with the exception of the slave girl Liù. But even she doesn’t appear to have what we would usually call a healthy outlook on life. The drama is described as a fairy tale or myth, and under those terms, one can of course accept that people make inexplicable decisions and behave oddly. But even in fairy tales, there must be somewhat credible reasons for why the characters have developed into the figures who populate the world of the drama. What kind of world might have shaped the characters in the opera Turandot?

The characters in Turandot live in a brutal society where the people in power have very little respect for human lives. They live in a closed-off world surrounded by walls. In closed societies, brutality easily develops according to its own laws. The wall, of course, serves a purpose. Walls—whether city walls or palace walls—are meant, like all other walls, to keep the unauthorized out. But walls always have dual functions. They may shut some people out, but at the same time, they shut others in. The city and palace walls of Turandot are important backdrops to the brutality of the society inhabited by the characters in the opera.

Of course, there are walls—and there are walls. All of them shut people in and out, but they can be given slightly different appearances. A white-painted wall might seem less unwelcoming than one built of grey, coarse granite blocks. A wall adorned with decorations looks less like a barrier than a damp brick wall. In this version of Turandot, the walls have been allowed to retain only their essential function: to prevent people from getting in or out. All social systems are complex—perhaps especially so in totalitarian societies. Tonight, we get a chance to see quite a bit of what happens in the shadows, behind the thick walls.

Sven Östberg

Set Designer